Numerous undo possibilities in Git

In this tutorial, we will show you different ways of undoing your work in Git, for which we will assume you have a basic working knowledge of. Check the GitLab Git documentation for reference.

Also, we will only provide some general information of the commands, which is enough to get you started for the easy cases/examples, but for anything more advanced please refer to the Git book.

We will explain a few different techniques to undo your changes based on the stage of the change in your current development. Also, keep in mind that nothing in Git is really deleted.

This means that until Git automatically cleans detached commits (which cannot be

accessed by branch or tag) it will be possible to view them with git reflog command

and access them with direct commit ID. Read more about redoing the undo in the section below.

For more information about working with Git and GitLab:

- Learn why North Western Mutual chose GitLab for their Enterprise source code management.

- Learn how to get started with Git.

Introduction

This guide is organized depending on the stage of development

where you want to undo your changes from and if they were shared with other developers

or not. Because Git is tracking changes a created or edited file is in the unstaged state

(if created it is untracked by Git). After you add it to a repository (git add) you put

a file into the staged state, which is then committed (git commit) to your

local repository. After that, file can be shared with other developers (git push).

Here's what we'll cover in this tutorial:

-

Undo local changes which were not pushed to a remote repository:

- Before you commit, in both unstaged and staged state.

- After you committed.

-

Undo changes after they are pushed to a remote repository:

- Without history modification (preferred way).

- With history modification (requires coordination with team and force pushes).

Branching strategy

Git is a de-centralized version control system, which means that beside regular versioning of the whole repository, it has possibilities to exchange changes with other repositories.

To avoid chaos with multiple sources of truth, various development workflows have to be followed, and it depends on your internal workflow how certain changes or commits can be undone or changed.

GitLab Flow provides a good balance between developers clashing with each other while developing the same feature and cooperating seamlessly, but it does not enable joined development of the same feature by multiple developers by default.

When multiple developers develop the same feature on the same branch, clashing with every synchronization is unavoidable, but a proper or chosen Git Workflow will prevent that anything is lost or out of sync when the feature is complete.

You can also read through this blog post on Git Tips & Tricks to learn how to easily do things in Git.

Undo local changes

Until you push your changes to any remote repository, they will only affect you. That broadens your options on how to handle undoing them. Still, local changes can be on various stages and each stage has a different approach on how to tackle them.

Unstaged local changes (before you commit)

When a change is made, but it is not added to the staged tree, Git itself proposes a solution to discard changes to a certain file.

Suppose you edited a file to change the content using your favorite editor:

vim <file>Since you did not git add <file> to staging, it should be under unstaged files (or

untracked if file was created). You can confirm that with:

$ git status

On branch master

Your branch is up-to-date with 'origin/master'.

Changes not staged for commit:

(use "git add <file>..." to update what will be committed)

(use "git checkout -- <file>..." to discard changes in working directory)

modified: <file>

no changes added to commit (use "git add" and/or "git commit -a")At this point there are 3 options to undo the local changes you have:

-

Discard all local changes, but save them for possible re-use later:

git stash -

Discarding local changes (permanently) to a file:

git checkout -- <file> -

Discard all local changes to all files permanently:

git reset --hard

Before executing git reset --hard, keep in mind that there is also a way to

just temporary store the changes without committing them using git stash.

This command resets the changes to all files, but it also saves them in case

you would like to apply them at some later time. You can read more about it in

section below.

Quickly save local changes

You are working on a feature when a boss drops by with an urgent task. Since your

feature is not complete, but you need to swap to another branch, you can use

git stash to save what you had done, swap to another branch, commit, push,

test, then get back to previous feature branch, do git stash pop and continue

where you left.

The example above shows that discarding all changes is not always a preferred option,

but Git provides a way to save them for later, while resetting the repository to state without

them. This is achieved by Git stashing command git stash, which in fact saves your

current work and runs git reset --hard, but it also has various

additional options like:

-

git stash save, which enables including temporary commit message, which will help you identify changes, among with other options -

git stash list, which lists all previously stashed commits (yes, there can be more) that were notpoped -

git stash pop, which redoes previously stashed changes and removes them from stashed list -

git stash apply, which redoes previously stashed changes, but keeps them on stashed list

Staged local changes (before you commit)

Let's say you have added some files to staging, but you want to remove them from the

current commit, yet you want to retain those changes - just move them outside

of the staging tree. You also have an option to discard all changes with

git reset --hard or think about git stash as described earlier.

Lets start the example by editing a file, with your favorite editor, to change the content and add it to staging

vim <file>

git add <file>The file is now added to staging as confirmed by git status command:

$ git status

On branch master

Your branch is up-to-date with 'origin/master'.

Changes to be committed:

(use "git reset HEAD <file>..." to unstage)

new file: <file>Now you have 4 options to undo your changes:

-

Unstage the file to current commit (HEAD):

git reset HEAD <file> -

Unstage everything - retain changes:

git reset -

Discard all local changes, but save them for later:

git stash -

Discard everything permanently:

git reset --hard

Committed local changes

Once you commit, your changes are recorded by the version control system. Because you haven't pushed to your remote repository yet, your changes are still not public (or shared with other developers). At this point, undoing things is a lot easier, we have quite some workaround options. Once you push your code, you'll have less options to troubleshoot your work.

Without modifying history

Through the development process some of the previously committed changes do not

fit anymore in the end solution, or are source of the bugs. Once you find the

commit which triggered bug, or once you have a faulty commit, you can simply

revert it with git revert commit-id.

This command inverts (swaps) the additions and deletions in that commit, so that it does not modify history. Retaining history can be helpful in future to notice that some changes have been tried unsuccessfully in the past.

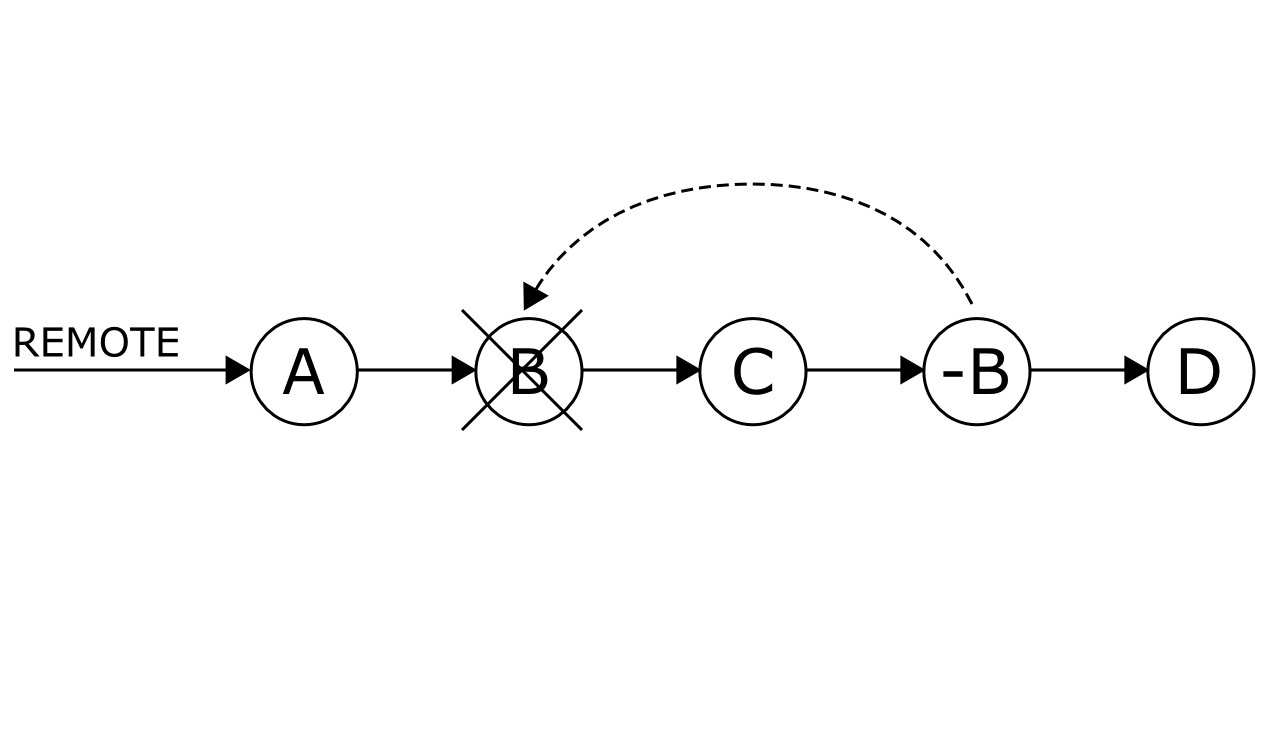

In our example we will assume there are commits A,B,C,D,E committed in this order: A-B-C-D-E,

and B is the commit you want to undo. There are many different ways to identify commit

B as bad, one of them is to pass a range to git bisect command. The provided range includes

last known good commit (we assume A) and first known bad commit (where bug was detected - we will assume E).

git bisect A..EBisect will provide us with commit ID of the middle commit to test, and then guide us

through simple bisection process. You can read more about it in official Git Tools

In our example we will end up with commit B, that introduced the bug/error. We have

4 options on how to remove it (or part of it) from our repository.

-

Undo (swap additions and deletions) changes introduced by commit

B:git revert commit-B-id -

Undo changes on a single file or directory from commit

B, but retain them in the staged state:git checkout commit-B-id <file> -

Undo changes on a single file or directory from commit

B, but retain them in the unstaged state:git reset commit-B-id <file> -

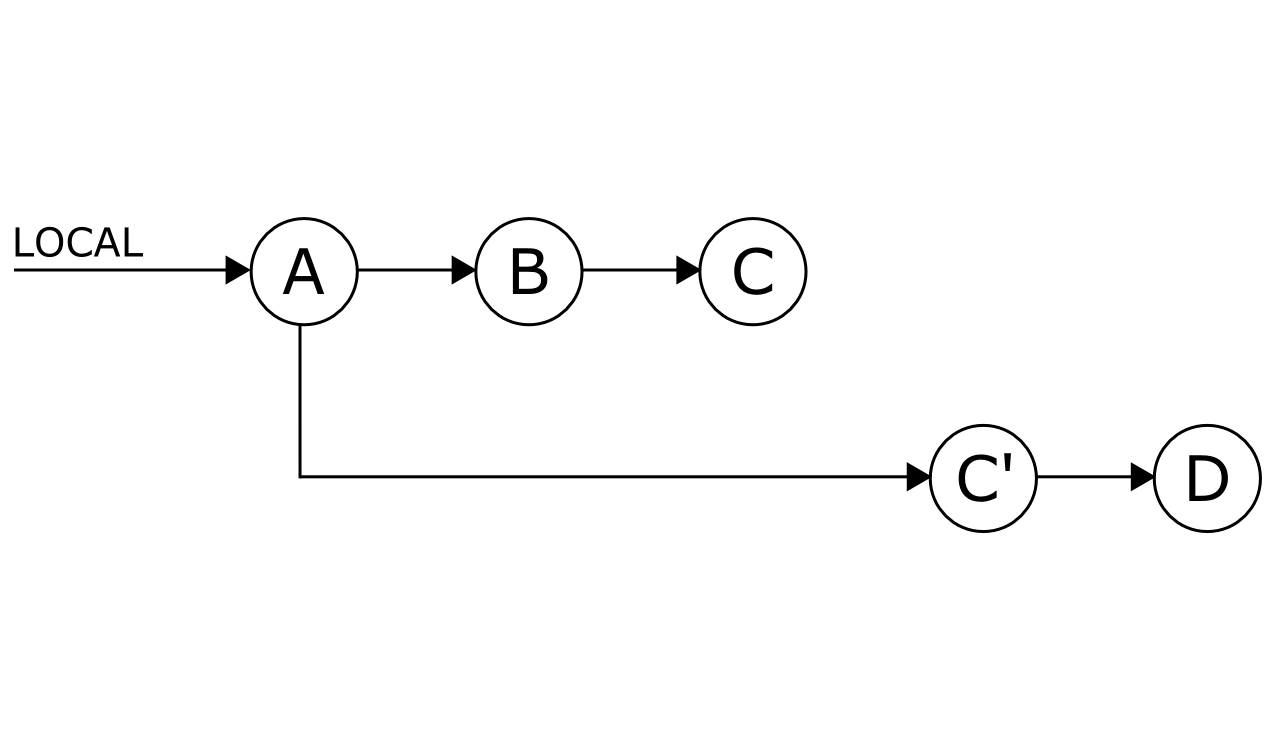

There is one command we also must not forget: creating a new branch from the point where changes are not applicable or where the development has hit a dead end. For example you have done commits

A-B-C-Don your feature-branch and then you figureCandDare wrong.At this point you either reset to

Band do commitF(which will cause problems with pushing and if forced pushed also with other developers) since branch now looksA-B-F, which clashes with what other developers have locally (you will change history), or you simply checkout commitBcreate a new branch and do commitF. In the last case, everyone else can still do their work while you have your new way to get it right and merge it back in later. Alternatively, with GitLab, you can cherry-pick that commit into a new merge request.git checkout commit-B-id git checkout -b new-path-of-feature # Create <commit F> git commit -a

With history modification

There is one command for history modification and that is git rebase. Command

provides interactive mode (-i flag) which enables you to:

-

reword commit messages (there is also

git commit --amendfor editing last commit message). - edit the commit content (changes introduced by commit) and message.

- squash multiple commits into a single one, and have a custom or aggregated commit message.

- drop commits - simply delete them.

- and few more options.

Let us check few examples. Again there are commits A-B-C-D where you want to

delete commit B.

-

Rebase the range from current commit D to A:

git rebase -i A -

Command opens your favorite editor where you write

dropin front of commitB, but you leave defaultpickwith all other commits. Save and exit the editor to perform a rebase. Remember: if you want to cancel delete whole file content before saving and exiting the editor

In case you want to modify something introduced in commit B.

-

Rebase the range from current commit D to A:

git rebase -i A -

Command opens your favorite text editor where you write

editin front of commitB, but leave defaultpickwith all other commits. Save and exit the editor to perform a rebase. -

Now do your edits and commit changes:

git commit -a

You can find some more examples in below section where we explain how to modify history

Redoing the Undo

Sometimes you realize that the changes you undid were useful and you want them

back. Well because of first paragraph you are in luck. Command git reflog

enables you to recall detached local commits by referencing or applying them

via commit ID. Although, do not expect to see really old commits in reflog, because

Git regularly cleans the commits which are unreachable by branches or tags.

To view repository history and to track older commits you can use below command:

$ git reflog show

# Example output:

b673187 HEAD@{4}: merge 6e43d5987921bde189640cc1e37661f7f75c9c0b: Merge made by the 'recursive' strategy.

eb37e74 HEAD@{5}: rebase -i (finish): returning to refs/heads/master

eb37e74 HEAD@{6}: rebase -i (pick): Commit C

97436c6 HEAD@{7}: rebase -i (start): checkout 97436c6eec6396c63856c19b6a96372705b08b1b

...

88f1867 HEAD@{12}: commit: Commit D

97436c6 HEAD@{13}: checkout: moving from 97436c6eec6396c63856c19b6a96372705b08b1b to test

97436c6 HEAD@{14}: checkout: moving from master to 97436c6

05cc326 HEAD@{15}: commit: Commit C

6e43d59 HEAD@{16}: commit: Commit BOutput of command shows repository history. In first column there is commit ID,

in following column, number next to HEAD indicates how many commits ago something

was made, after that indicator of action that was made (commit, rebase, merge, ...)

and then on end description of that action.

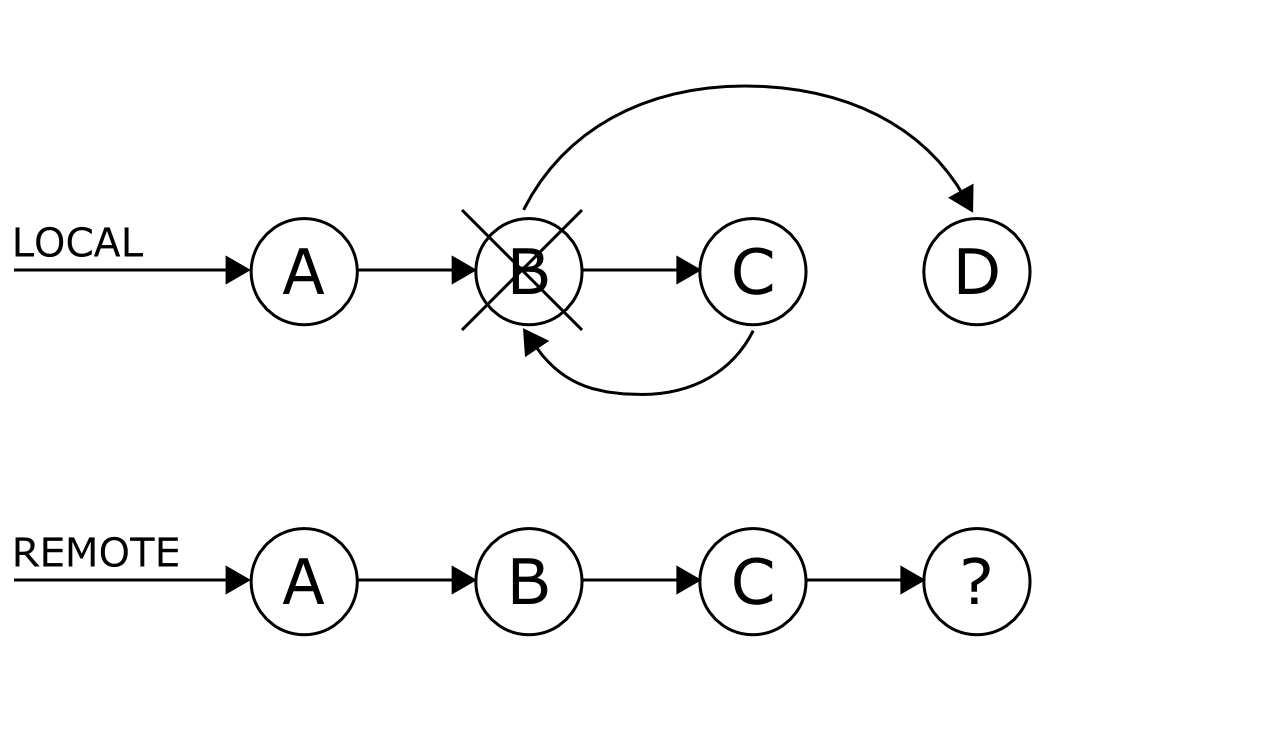

Undo remote changes without changing history

This topic is roughly same as modifying committed local changes without modifying history. It should be the preferred way of undoing changes on any remote repository or public branch. Keep in mind that branching is the best solution when you want to retain the history of faulty development, yet start anew from certain point.

Branching enables you to include the existing changes in new development (by merging) and it also provides a clear timeline and development structure.

If you want to revert changes introduced in certain commit-id you can simply

revert that commit-id (swap additions and deletions) in newly created commit:

You can do this with

git revert commit-idor creating a new branch:

git checkout commit-id

git checkout -b new-path-of-featureUndo remote changes with modifying history

This is useful when you want to hide certain things - like secret keys, passwords, SSH keys, etc. It is and should not be used to hide mistakes, as it will make it harder to debug in case there are some other bugs. The main reason for this is that you loose the real development progress. Also keep in mind that, even with modified history, commits are just detached and can still be accessed through commit ID - at least until all repositories perform the cleanup of detached commits (happens automatically).

Where modifying history is generally acceptable

Modified history breaks the development chain of other developers, as changed history does not have matching commit IDs. For that reason it should not be used on any public branch or on branch that might be used by other developers. When contributing to big open source repositories (for example, GitLab itself), it is acceptable to squash commits into a single one, to present a nicer history of your contribution.

Keep in mind that this also removes the comments attached to certain commits in merge requests, so if you need to retain traceability in GitLab, then modifying history is not acceptable.

A feature-branch of a merge request is a public branch and might be used by

other developers, but project process and rules might allow or require

you to use git rebase (command that changes history) to reduce number of

displayed commits on target branch after reviews are done (for example

GitLab). There is a git merge --squash command which does exactly that

(squashes commits on feature-branch to a single commit on target branch

at merge).

NOTE:

Never modify the commit history of master or shared branch.

How modifying history is done

After you know what you want to modify (how far in history or how which range of

old commits), use git rebase -i commit-id. This command will then display all the commits from

current version to chosen commit ID and allow modification, squashing, deletion

of that commits.

$ git rebase -i commit1-id..commit3-id

pick <commit1-id> <commit1-commit-message>

pick <commit2-id> <commit2-commit-message>

pick <commit3-id> <commit3-commit-message>

# Rebase commit1-id..commit3-id onto <commit4-id> (3 command(s))

#

# Commands:

# p, pick = use commit

# r, reword = use commit, but edit the commit message

# e, edit = use commit, but stop for amending

# s, squash = use commit, but meld into previous commit

# f, fixup = like "squash", but discard this commit's log message

# x, exec = run command (the rest of the line) using shell

# d, drop = remove commit

#

# These lines can be re-ordered; they are executed from top to bottom.

#

# If you remove a line here THAT COMMIT WILL BE LOST.

#

# However, if you remove everything, the rebase will be aborted.

#

# Note that empty commits are commented outNOTE: It is important to notice that comment from the output clearly states that, if you decide to abort, then do not just close your editor (as that will in-fact modify history), but remove all uncommented lines and save.

That is one of the reasons why git rebase should be used carefully on

shared and remote branches. But don't worry, there will be nothing broken until

you push back to the remote repository (so you can freely explore the

different outcomes locally).

# Modify history from commit-id to HEAD (current commit)

git rebase -i commit-idDeleting sensitive information from commits

Git also enables you to delete sensitive information from your past commits and

it does modify history in the progress. That is why we have included it in this

section and not as a standalone topic. To do so, you should run the

git filter-branch, which enables you to rewrite history with

certain filters.

This command uses rebase to modify history and if you want to remove certain

file from history altogether use:

git filter-branch --tree-filter 'rm filename' HEADSince git filter-branch command might be slow on big repositories, there are

tools that can use some of Git specifics to enable faster execution of common

tasks (which is exactly what removing sensitive information file is about).

An alternative is the open source community-maintained tool BFG.

Keep in mind that these tools are faster because they do not provide the same

feature set as git filter-branch does, but focus on specific use cases.

Refer Reduce repository size page to know more about purging files from repository history & GitLab storage.

Conclusion

There are various options of undoing your work with any version control system, but because of de-centralized nature of Git, these options are multiplied (or limited) depending on the stage of your process. Git also enables rewriting history, but that should be avoided as it might cause problems when multiple developers are contributing to the same codebase.